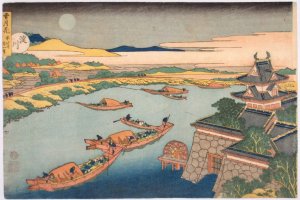

Ukiyo-e woodblock prints are a typically Japanese art form, depicting scenes from the ‘Floating World’ such as theaters and teahouses, geisha and cherry-blossoms. They were developed during the Edo period from the 1620s, and became popular in western countries after Japan opened to foreign trade in 1867, influencing artists such as Toulouse-Lautrec and van Gogh. Company chairman and philanthropist Ota Seizo dedicated himself to their collection and preservation, and in his lifetime amassed a collection of some 12,000 prints, which are now held and displayed at the museum which bears his name.

The first thing I did at the entrance was take my shoes off, as if I were entering a Japanese home; this made me feel more like a guest than a customer, creating the sense that I was being welcomed to a place of friendly calm. So it proved to be: the interior felt as serene as any Japanese temple, with a raised tatami alcove, and a small replica garden seat complete with bamboo screen and lantern. The low lighting necessary to maintain the prints’ condition added to the tranquil atmosphere.

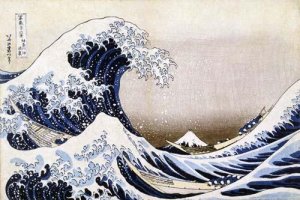

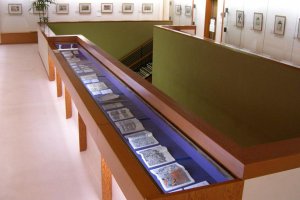

Owing to the size of the collection and the delicacy of the prints, they are displayed in themed exhibitions of about 80-100 at a time, rotated every month. (The museum is closed for a few days at the end of each month while the exhibitions are changed: you can see a detailed schedule here, along with details of the admission fees for each exhibition.) On my visit I was fortunate enough to be able to see Hokusai’s iconic ‘The Great Wave off Kanagawa’, perhaps the best known of all ukiyo-e.

There were plenty of other prints on display by Hokusai and Hiroshige, two giants of the art form, as well as by numerous other artists; the new year theme allowed for a range of different subjects, and the English explanations cast light on the traditional activities portrayed, such as traveling female singers, and sellers of treasure-ship images for placing under childrens’ pillows to ensure a prosperous year. Despite their antiquity, the prints had preserved their bright colors, with vibrant splashes of jade and crimson adding life to the scenes.

Something else I enjoyed was the display on the printing process itself: using the ‘Great Wave’ as an example, it illustrates in detail how the woodblocks are prepared and the image gradually built up, color by color. This provided for me an interesting insight into the painstaking nature of the creation of a print, and made me appreciate more the talent of the artists.

The museum is located on a quiet side-street off Omotesando-dori, so it’s worth tearing yourself away from the shops and enjoying a taste of Japanese art history, to become acquainted with the floating world.